Flask is a powerful and flexible micro web framework for Python, ideal for both small and large web projects. It provides a straightforward way to get a web application up and running, with all the features that you need to get started.

Over the course of this tutorial, you’ll explore the process of creating a boilerplate for a Flask web project. This boilerplate will serve as a great starting point for any scalable Flask web app that you wish to develop in the future, from basic web pages to complex web applications.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to:

At the end of this tutorial, you’ll have created a working Flask web application that you can use to bootstrap your future Flask projects.

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free source code that shows you how to build a Flask project boilerplate.

You don’t need any previous knowledge of Flask to complete this project. If you want to learn more about the topics that you encounter in this tutorial, then you’ll find links to resources along the way.

However, you should be comfortable using the terminal and have basic knowledge of Python. Although it helps to know about virtual environments and pip , you’ll learn how to set everything up as you work through the tutorial.

In this tutorial, you’ll start building a Flask project, which could become a public message board at some point. Here’s what the project will look at the end of this tutorial:

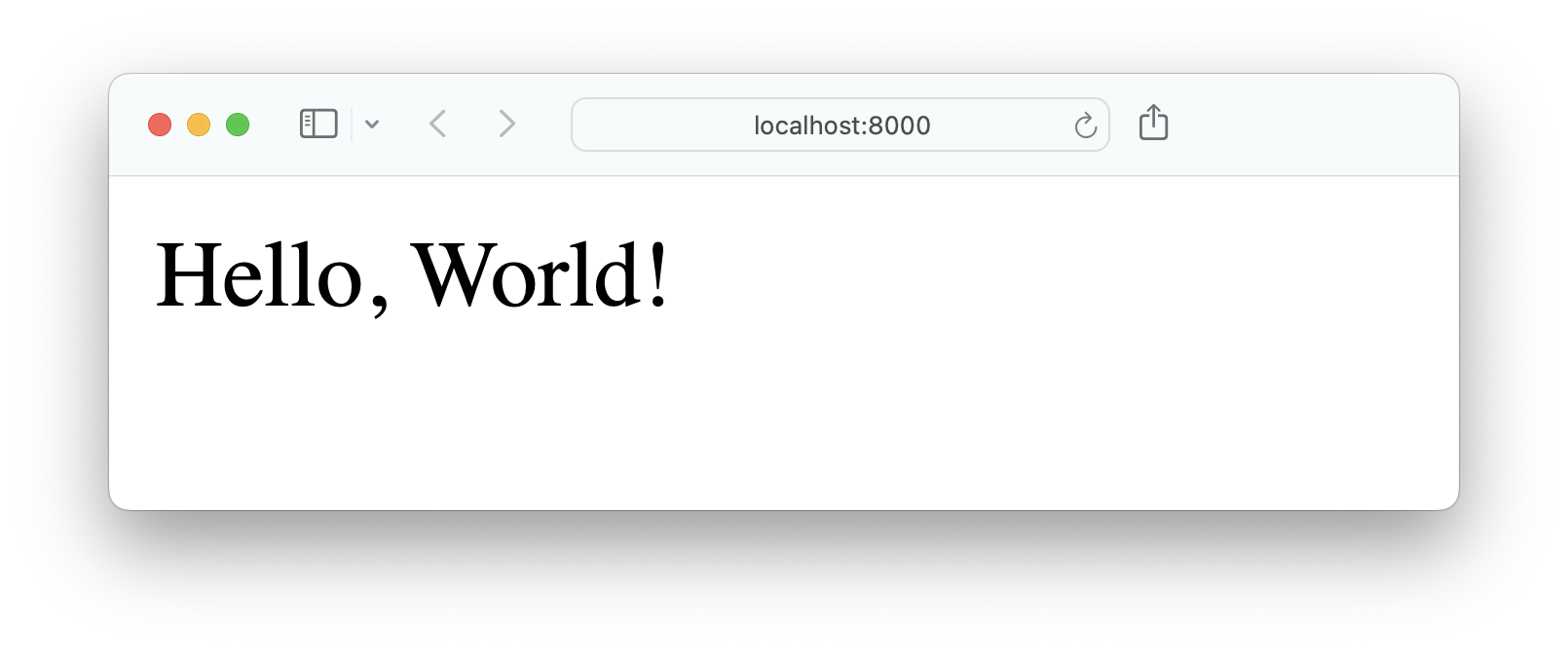

Congratulations, your web server is running! You can stop the development server by pressing Ctrl + C in your terminal.

Your current project structure is great for starting a Flask project. However, if you want to work on bigger projects, this structure can be limiting because you’d need to add more and more code to app.py . Instead, you’ll adjust the structure a bit to create a more scalable Flask project.

Packages are useful for structuring Python code into logical groupings for large programs. Because your web project can grow large, too, transforming your project into a package makes sense. Since you’re just at the start of the project, your to-do list to create the package has only three tasks:

You can perform these tasks by hand or use the terminal to perform all three steps with two commands:

(venv) $ mkdir board (venv) $ mv app.py board/__init__.py With the commands above, you create the board/ subfolder. Then, you move app.py into board/ and rename it to __init__.py .

By now, your Flask project structure should look like this:

rp_flask_board/ │ └── board/ └── __init__.py With the new package structure in place, make sure that you stay in the rp_flask_board/ folder and run your Flask project with this command:

(venv) $ python -m flask --app board run --port 8000 --debug With the command above, you’re telling Flask to look for an app named board and serve it in debug mode on port 8000 . When you visit http://localhost:8000 , you see the same Hello, World! displayed as before.

An application factory in Flask is a design pattern that’s highly beneficial for scaling Flask projects. With an application factory, you can create and configure your Flask project flexibly and efficiently, making it easier to develop, test, and maintain as it grows and evolves.

Instead of having your application’s code at the root level of your __init__.py file, you’ll work with a function that returns your application. To do so, replace the content of __init__.py with the content below:

Python board/__init__.pyfrom flask import Flask def create_app(): app = Flask(__name__) return app After importing Flask , you create a function named create_app() that initializes the app and returns it. The create_app() function is your application factory.

With an application factory, your project’s structure becomes more organized. It encourages you to separate different parts of your application, like routes, configurations, and initializations, into different files later on. This encourages a cleaner and more maintainable codebase.

To see the benefits of an application factory in action, you’ll create your first blueprint in the next section.

As your Flask project grows, you have lots of view functions and other related bits of code that work together. Instead of adding all these directly to a basic app.py file, you can create blueprints that you register in your application factory.

Blueprints are modules that contain related views that you can conveniently import in __init__.py . For example, you’ll have a blueprint that stores the main pages of your project.

Create a file named pages.py in the board/ folder and add the content below:

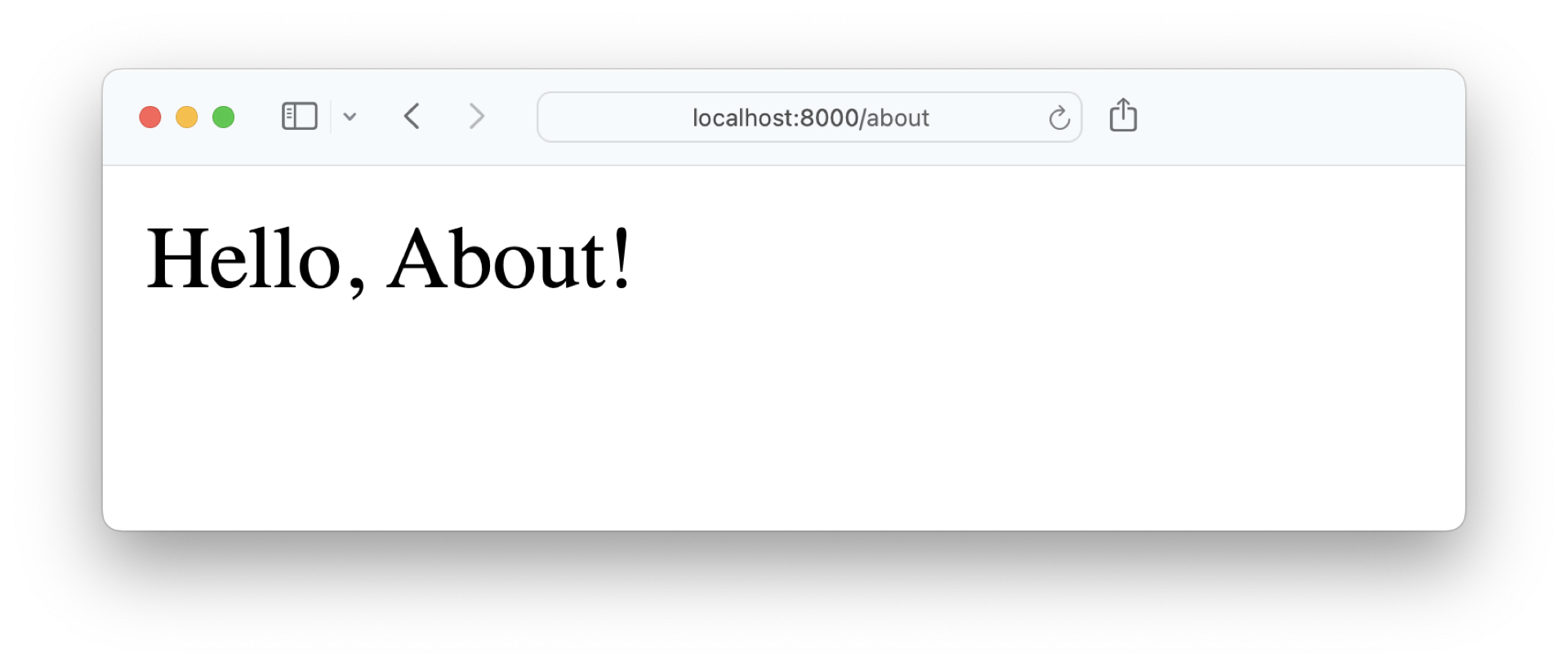

Python board/pages.pyfrom flask import Blueprint bp = Blueprint("pages", __name__) @bp.route("/") def home(): return "Hello, Home!" @bp.route("/about") def about(): return "Hello, About!" After importing Blueprint , you create an instance of it named bp . The first argument, "pages" , is the name of your blueprint. You’ll use this name to identify this particular blueprint in your Flask project. The second argument is the blueprint’s __name__ . You’ll use this later when you import pages into __init__.py .

Then, you define two routes, one as the home view and the other as the about view. Each of them returns a string to indicate on which page you are on.

Before you can visit the pages, you need to connect the pages blueprint with your Flask project:

Python board/__init__.pyfrom flask import Flask from board import pages def create_app(): app = Flask(__name__) app.register_blueprint(pages.bp) return app Once you’ve imported and registered the pages blueprint in your application factory, you can visit the routes that you defined in pages.py in your browser. When you visit http://localhost:8000/about , then you can see the Hello, About! string:

If the main purpose of your Flask project were to just display plain strings, then you’d be done. However, it’s more fun to actually display dynamic content to your users. That’s when templates come into play.

Templates are HTML files with the capability of rendering dynamic content sent over from your Flask views. For this, Flask uses the popular Jinja template engine, which you already installed as a dependency when you installed Flask.

With a template engine like Jinja, you can embed Python-like expressions into your templates to create dynamic web content. You can use loops, conditionals, and variables directly in your templates.

Jinja also supports template inheritance, allowing the creation of a base template that you can extend in child templates, promoting code reuse and a consistent layout across different pages of your project.

Create a new template named base.html in a templates/ directory inside board/ :

HTML board/templates/base.html 1 2html lang="en"> 3head> 4 title>Message Board - block title %> endblock title %>title> 5head> 6body> 7h1>Message Boardh1> 8section> 9 header> 10 block header %> endblock header %> 11 header> 12 main> 13 block content %>p>No messages.p> endblock content %> 14 main> 15section> 16body> 17html> Commonly, the Jinja base template is named base.html , and it contains the main HTML structure of your web pages. The main structure of base.html is similar to a normal HTML page. You start by declaring the doctype, wrapping everything in tags, and setting the lang attribute.

Then you go on to add and with some other nested elements. In line 4, you set the title of your project to Message Board. The empty title block gives you the opportunity to extend the title with a child template.

Note: The message board is just an example for a generic Flask project. Feel free to give your Flask project a more fitting name.

In line 10, you set the header block. If a child template doesn’t contain a header block, then will stay empty.

By providing default content inside the content block in line 13, you either display the No messages hint or show the content of the child template.

Your base template is designed to provide a consistent structure for your project while allowing flexibility in specific parts of the content through Jinja’s block functionality. Next, create the child templates that extend base.html and fill in these blocks with their specific content.

Start with the template for your home view by creating a home.html file in a pages/ subfolder of your templates/ folder:

HTML board/templates/pages/home.html 1 extends 'base.html' %> 2 3 block header %> 4 h2> block title %>Home endblock title %>h2> 5 endblock header %> 6 7 block content %> 8 p> 9 Learn more about this project by visiting the a href=" <url_for('pages.about') >>">About pagea>. 10 p> 11 endblock content %> To connect the child template with its parent template, you must add an tag at the top of the file.

Child templates also contain tags. By providing the block’s name as an argument, you’re connecting the blocks from the child template with the blocks from the parent template.

When you use url_for() , Flask creates the full URL to the given view for you. This means that if you change the route in your Python code, then the URL in your templates updates automatically.

Continue by creating a file named about.html in the same pages/ directory:

HTML board/templates/pages/about.html 1 extends 'base.html' %> 2 3 block header %> 4 h2> block title %>About endblock title %>h2> 5 endblock header %> 6 7 block content %> 8 p>This is a message board for friendly messages.p> 9 endblock content %> Just like in home.html , you do something nifty with the title block. You add the page’s title inside the header block and wrap it within title . Jinja will understand this structure and render the page’s title in the header and title blocks.

With both child templates in place, you need to adjust your views to return the templates instead of the plain strings. Hop over to pages.py and adjust home() and about() :

Python board/pages.pyfrom flask import Blueprint, render_template bp = Blueprint("pages", __name__) @bp.route("/") def home(): return render_template("pages/home.html") @bp.route("/about") def about(): return render_template("pages/about.html") After importing Flask’s render_template() , you can use the function to return the home.html and about.html templates that you placed in the templates/pages/ folder.

By default, Flask expects your templates to be in a templates/ directory. Therefore, you don’t need to include templates/ in the path of the templates.

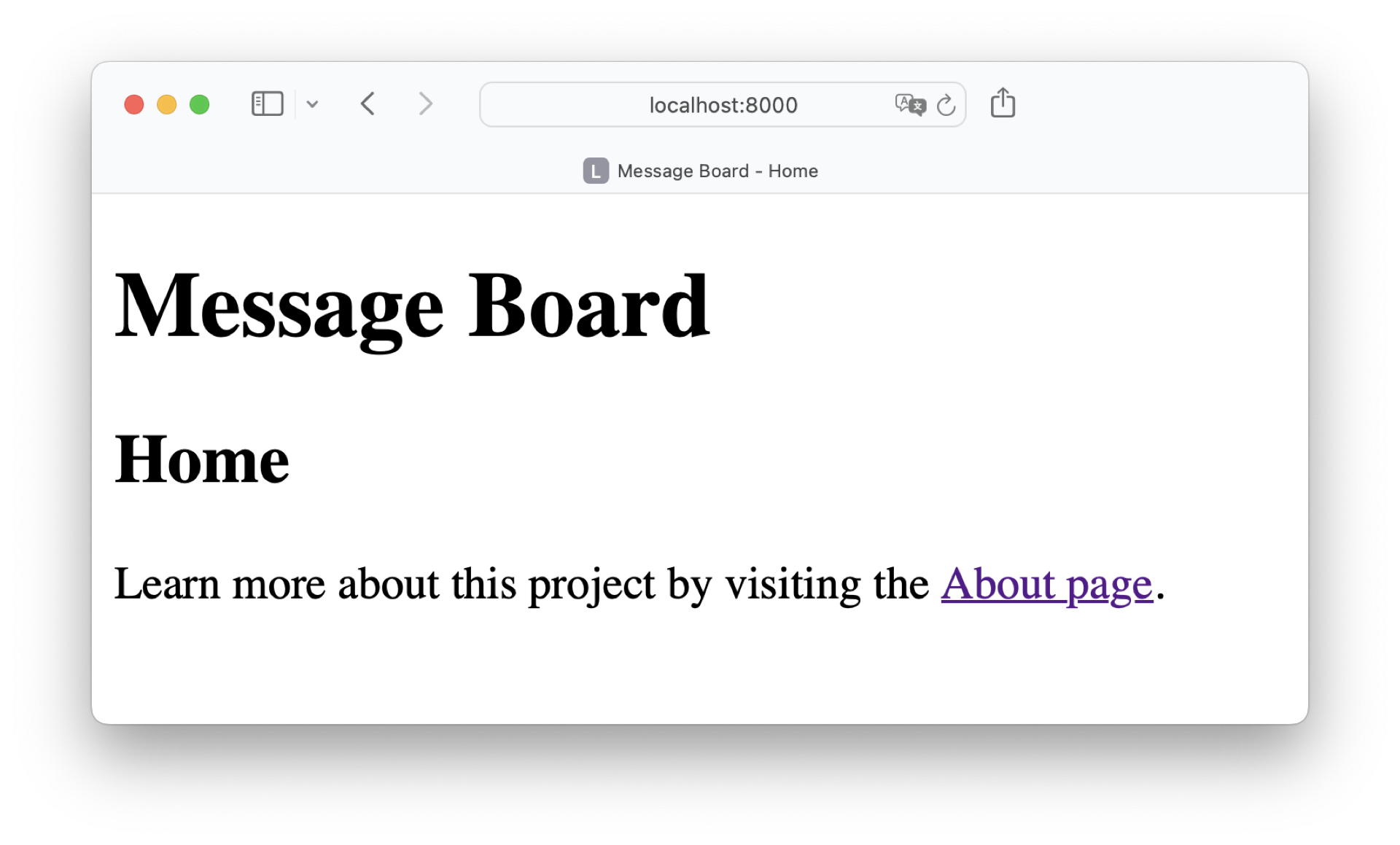

To verify that your templates work, restart your Flask development server and visit http://localhost:8000 :

Your Home page shows the dynamic title.

When you visit your Home page, then you can click the link to the About page. Since there’s no link to the Home page, you’d need to either use the Back button of your browser or enter the URL manually in the address bar.

It seems like it’s time to elevate the user experience and include a navigation menu in your project!

A good user experience is crucial in any web application. It ensures that users find the application not only convenient to use, but also enjoyable.

In the upcoming sections, you’ll add a navigation menu and style your web application. While doing so, notice how these additions can contribute to a better user experience.

The navigation of a website is usually displayed on every page. With your base and child template structure, it’s best to add the code for the navigation menu into base.html .

Instead of adding the navigation menu code directly into base.html , you can leverage the tag. By referencing another template with , you’re loading the whole template into that position. If you need to make any changes in the navigation, then you know exactly where to look. Additionally, you can decide to include your navigation template on a different part of the page, for example when you design a 404 error template.

Included templates are partials that contain a fraction of the full HTML code. To indicate that a template is meant to be included, you can prefix its name with an underscore ( _ ).

Follow the prefix-based naming scheme and create a new template named _navigation.html in your templates/ folder:

HTML templates/_navigation.htmlnav> ul> li>a href=" <url_for('pages.home') >>">Homea>li> li>a href=" <url_for('pages.about') >>">Abouta>li> ul> nav> Note that _navigation.html contains neither an tag nor any tags. You can focus solely on how you want to render your navigation menu.

Just like above, you use url_for() , and Flask creates the full URL to the given view for you. So, even when you decide to change the route to one of your pages, the navigation menu will still work.

Include _navigation.html in base.html to display your navigation menu on all of your pages:

HTML templates/base.html html lang="en"> head> title>Message Board - block title %> endblock title %>title> head> body> h1>Message Boardh1> include("_navigation.html") %> section> header> block header %> endblock header %> header> main> block content %>p>No messages.p> endblock content %> main> section> body> html> Instead of adding the navigation menu code directly into base.html , you include _navigation.html in your website’s header.

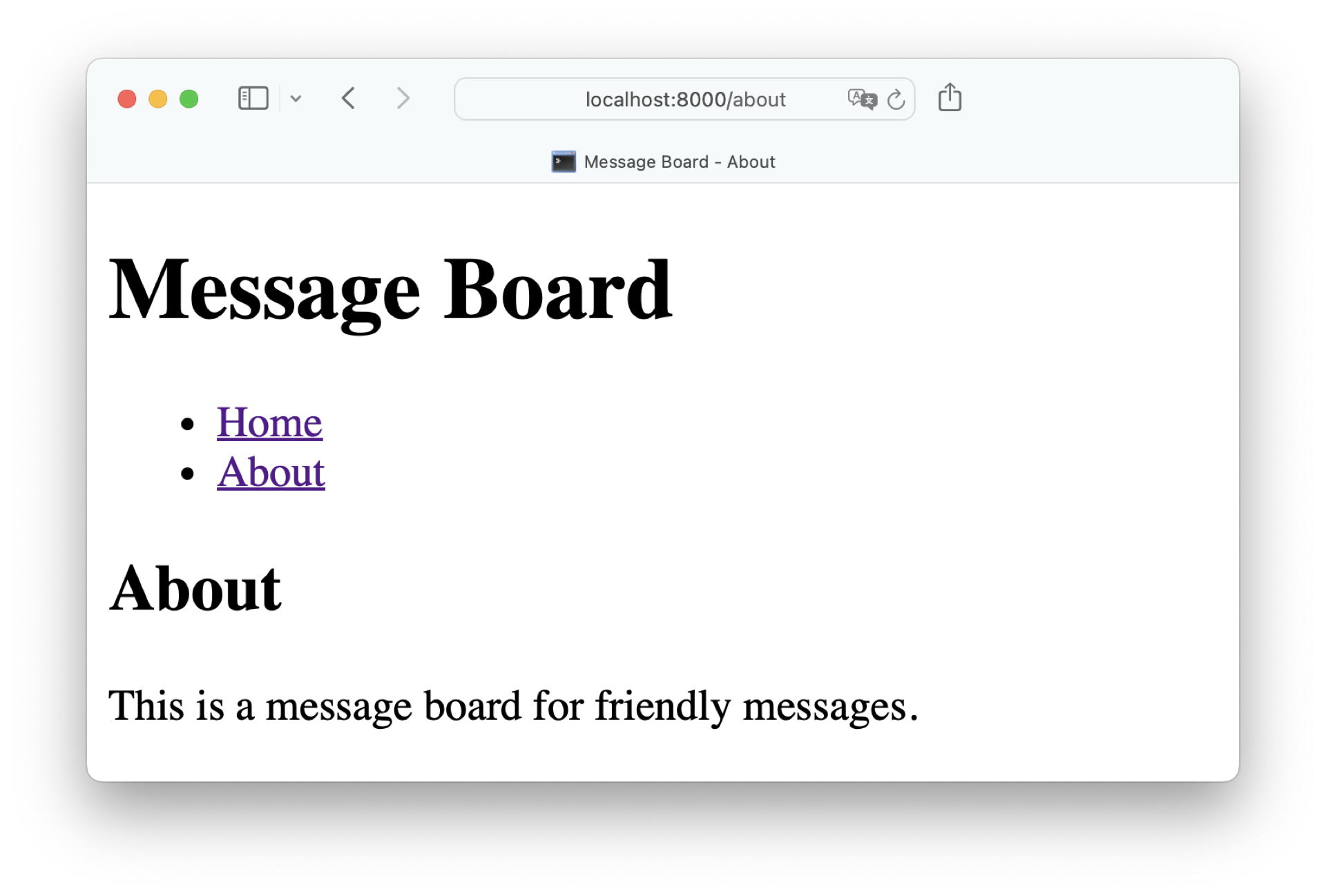

Visit http://localhost:8000/about to check out your new navigation menu:

Since both home.html and about.html extend base.html , you didn’t need to make any changes in these templates to make the navigation menu appear. That’s template inheritance in action!

But wait, there’s more! In the next section, you’ll leverage template inheritance to add consistent styling to your web project.

The templates in your project provide the logic and structure for the front end of your project. With the help of Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), you can style the content.

In Flask projects, you commonly save CSS files in a static/ directory. In this project, you’ll only work with one CSS file named styles.css . But if you decide to expand the project at some point, you can also use this folder to store images or JavaScript files.

Create a new directory named static/ inside of board/ and place a file named styles.css in it with the CSS declarations below:

CSS board/static/styles.css* box-sizing: border-box; > body font-family: sans-serif; font-size: 20px; margin: 0 auto; text-align: center; > a, a:visited color: #007bff; > a:hover color: #0056b3; > nav ul list-style-type: none; padding: 0; > nav ul li display: inline; margin: 0 5px; > main width: 80%; margin: 0 auto; > The CSS declarations above ensure that the web elements are properly spaced and sized, making the website look organized and more convenient to navigate.

The color scheme for the links provides a visual cue to users about clickable elements. The font choice and size contribute to readability. The overall layout and alignment of the web elements give the website a clean and modern look.

With the style sheet in place, you need to add a link to styles.css inside of base.html :

HTML templates/base.html html lang="en"> head> title>Message Board - block title %> endblock title %>title> link rel="stylesheet" href=" <url_for('static', filename='styles.css') >>"> head> body> body> html> You can reference a CSS file with a tag in the header of your HTML page. Just like before, you use url_for() to create the full URL for the href attribute. To link to the styles.css file stored in your Flask project’s static/ folder specifically, you use the filename argument.

By adding the CSS file reference to base.html , you’re again taking advantage of the inheritance mechanism that Jinja templates provide. You only need to add styles.css in your base template to make it present in your child templates.

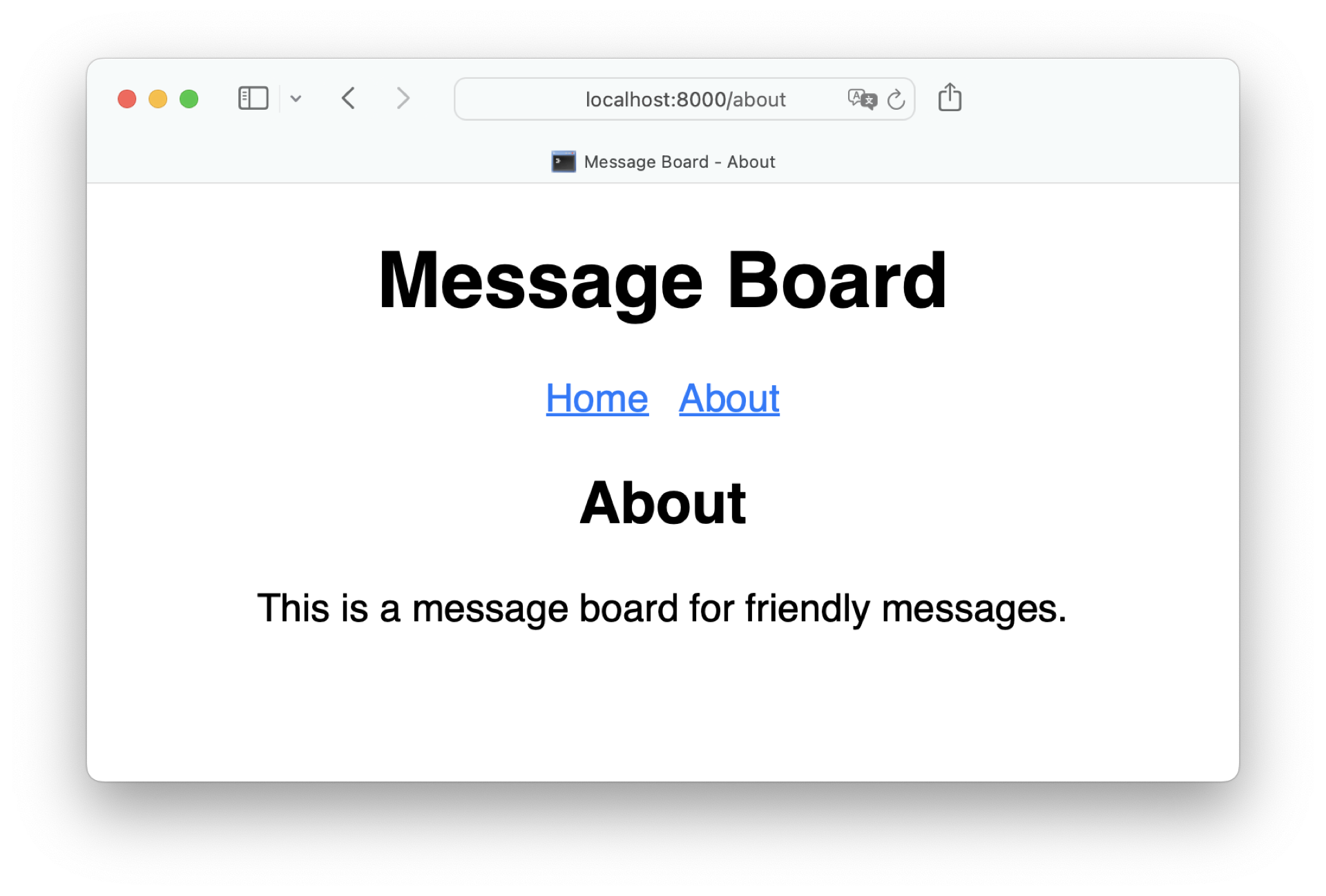

You may need to restart your Flask development server again to see your styling in action:

With some minimal styling, your Flask web project is starting to look like a finished web app. Feel free to add more pages and content on your own. Once you’re finished, you can continue to work on the message board project by adding a database and accepting posts from your users.

Congratulations on successfully setting up a Flask project. This working Flask web project is a great starting point for any future Flask projects that you may have. By understanding these foundational concepts, you’re now well equipped to tackle more complex projects and further explore the capabilities of Flask.

In this tutorial, you’ve learned how to:

You’ve successfully created a working Flask web application that you can use to bootstrap your future Flask projects.

Do you already have a cool Flask project in mind? Let the Real Python community know in the comments below!

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free source code that shows you how to build a Flask project boilerplate.

Mark as CompletedGet a short & sweet Python Trick delivered to your inbox every couple of days. No spam ever. Unsubscribe any time. Curated by the Real Python team.

About Philipp Acsany

Philipp is a core member of the Real Python team. He creates tutorials, records video courses, and hosts Office Hours sessions to support your journey to becoming a skilled and fulfilled Python developer.

Each tutorial at Real Python is created by a team of developers so that it meets our high quality standards. The team members who worked on this tutorial are:

Master Real-World Python Skills With Unlimited Access to Real Python

Join us and get access to thousands of tutorials, hands-on video courses, and a community of expert Pythonistas:

Master Real-World Python Skills

With Unlimited Access to Real Python

Join us and get access to thousands of tutorials, hands-on video courses, and a community of expert Pythonistas:

What Do You Think?

Rate this article:What’s your #1 takeaway or favorite thing you learned? How are you going to put your newfound skills to use? Leave a comment below and let us know.

Commenting Tips: The most useful comments are those written with the goal of learning from or helping out other students. Get tips for asking good questions and get answers to common questions in our support portal. Looking for a real-time conversation? Visit the Real Python Community Chat or join the next “Office Hours” Live Q&A Session. Happy Pythoning!